Ice Buddha

Lhasa, U region, central Tibet (TAR, China) 2006Gade (b. 1971, Lhasa); Ice Buddha No. 1 (8 photographs); Lhasa; 2006; chromogenic prints; each 31½ × 19-5/8 in. (80 × 50 cm); photographs by Jason Sangster, courtesy Gade

Gade (b. 1971, Lhasa); Ice Buddha No. 1 (8 photographs); Lhasa; 2006; chromogenic prints; each 31½ × 19-5/8 in. (80 × 50 cm); photographs by Jason Sangster, courtesy Gade

Gade (b. 1971, Lhasa); Ice Buddha No. 1 (8 photographs); Lhasa; 2006; chromogenic prints; each 31½ × 19-5/8 in. (80 × 50 cm); photographs by Jason Sangster, courtesy Gade

Tibetan art has ancient roots, but Tibetan artists also embrace contemporary methods, forms, and realities. Art historians Yangla Gesang, Yuyuan (Victoria) Liu, and Elena Pakhoutova explore today’s vibrant Tibetan art world, from alternative collectives in Lhasa and expatriate artists in India and Nepal, to internationally based artists in Europe and the United States. Different generations of these artists use modern methods, and express and comment on the increasingly complex contemporary Tibetan world.

In Buddhism and Bon, a buddha is understood as a being who practices good deeds for many lifetimes, and finally, through intense meditation, achieves nirvana, or ”awakening”—a state beyond suffering, free from the cycle of birth and death. “The Buddha” of our age is Shakyamuni, or Siddhartha Gautama. He is considered the founding teacher of the religion we call Buddhism. The buddha prior to Shakyamuni was called Dipamkara, and the next buddha will be Maitreya. These are known as Buddhas of the Three Times. Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists believe that there are infinite buddhas in infinite universes, who have many bodies or emanations. Other important buddhas include Amitabha, Vairochana, Bhaishajyaguru, Maitreya, and many more.

Emptiness is a core concept of the Madhyamaka philosophical tradition of Mahayana Buddhism, most famously formulated by the Indian philosopher Nagarjuna (ca. second to third century CE) and elaborated by Chandrakirti (c. seventh century CE). Emptiness (Skt. shunyata) refers to the absence of inherent existence, meaning that although all things, including the self, exist insofar as we perceive them, they are constantly changing and dependent on causes and conditions, and thus empty of inherent existence. Buddhas are said to perceive both of these relative and absolute truths at once. Other Buddhist traditions, for instance Dzogchen and the Jonang, interpret emptiness as a primordial state of radiant awareness underlying the phenomenal world.

Impermanence is a core concept in Buddhism. The Buddha taught that all beings, things, and thoughts are constantly appearing, changing, and passing away in samsara. We suffer because we are attached to these unstable things. In Madhyamaka philosophy, impermanence is a central part of the doctrine of emptiness.

A pecha is a traditional form of Tibetan book, a format developed from Indian palm leaf manuscripts (pothis). Pechas usually have long, narrow, horizontal pages. The pages are not bound, but instead are placed between wood covers and then wrapped tightly with cloth. When pechas are read, they are placed on a flat surface and the unbound pages are flipped over away from the viewer. Pechas can be manuscripts or printed.

Stupas are monuments that initially contained cremated remains of Buddha Shakyamuni or important monks, his disciples, and subsequently other material and symbolic relics associated with the Buddha’s body, teaching, and enlightened mind. As representations of the Buddha’s presence in the world, stupas with their contents—texts, relics, tsatsas—continue to be important objects of Buddhist worship in their diverse forms of domed structures, multistoried pagodas, and portable sculptures. The original form of stupas was an earthen dome-shaped mound containing the remains in reliquary vessels or urns deposited within the innermost core. The dome would often be successively enlarged and surrounded by a path for a walk around in a clockwise direction and veneration (circumambulation)

The Tibetan script is used to write the Tibetan language, as well as several other smaller Himalayan languages. Based on the Brahmi script used in the Gupta Empire in India, the Tibetan script was developed under the Tibetan Empire in the seventh century and is credited to minister Tonmi Sambhota (b. 619?). Two important forms of the Tibetan script are “Uchen” (Tib. “having a head”), a standard type used in printed texts, and “Umey” (Tib. “headless”), a cursive form sometimes used in manuscripts. There are many other cursive and decorative forms of the script.

In the placid and reflective surface of the water sits a glittering, translucent statue of a made of ice, with the Potala Palace in the background. Under the scorching sunlight, Ice Buddha gradually melts and sinks into the river.

Eight photographs document the 2006 conceptual installation by the artist Gade (fig. 1). He collected water from the Kyichu River, which flows through the city of Lhasa, froze the water, and, following traditional proportions and visual conventions, sculpted the ice into a statue of . As the statue melted, the river’s own water returned to its source, which flows through India—where originated before it was introduced to Tibet—eventually reaching the Indian Ocean.

In Ice Buddha Gade uses the most recognizable Buddhist symbol and the temporality of water as his medium. He connects the water’s changing forms, from liquid to solid ice and back to water, with the Buddhist philosophical concepts of impermanence and reincarnation in the karmically driven cycle of successive existences (). The artist preserves the essence of the Buddha’s form, but moves away from the traditional formats of two-dimensional painting and static metal sculpture to performative aspects and installation in nature, using impermanent media not previously explored in emerging Tibetan contemporary art.

Viewers can read much into this work’s multilayered meaning. The connotations it evokes range from the purely philosophical to the culturally astute, socially relevant, and personally evocative. To name a few: , the cyclical nature of existence and reincarnation; the fragility of traditional cultural values; the dissolution of Tibetan Buddhist culture; change; and reflections on the passage of time.

The buddha is the most representative visual form and religious symbol associated with contemplative qualities. A buddha’s form embodies Buddhist teachings on the nature of reality, and universal philosophical notions of impermanence and , as well as cultural practices and personal connections to the teachings (). Contemporary Tibetan artists explore and often contest the richly symbolic religious and cultural associations of this form.

Around the turn of the twenty-first century, several artists engaged the buddha’s form in ways that challenged assumptions and preconceptions about Tibetan Buddhist culture. Their work addressed on the one hand, the loss of traditional culture and the pervasiveness of popular culture with its new icons, and on the other hand, consumption of Buddhist images and the “commercialization” of . In his earlier works, Gonkar Gyatso, an artist based in the United Kingdom and China, used colorful stickers and commercial logos to fill an outlined buddha’s head, replacing the buddha’s features. For a 2010 work titled Do What You Love, he made a three-dimensional scan of a traditionally cast fourteenth-century sculpture, digitally manipulated the image, and mass-produced buddha figures, positioning them with their heads stuck in the wall and their backs toward the viewer (fig. 2). Other artists, including the Lhasa-based Nortse and Angsang, and the US-based Ang Tsherin Sherpa and Tenzing Rigdol, have addressed various aspects of their present-day lives through the images of the buddha’s form.

Gonkar Gyatso (b. 1961, Lhasa); Do What You Love; 2010; bronze and polyester resin; 27 buddhas, ea. 16 × 16½ × 10 in. (40.6 × 41.9 × 25.4 cm); installation view, Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art; 2010; photograph by David De Armas, courtesy Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art

Artists have also reinterpreted another recognizable Buddhist symbol that represents the Buddha’s mind, the . The US-based Palden Weinreb, in his Untitled (Stupa), created in encaustic wax and made luminous from within by LED lights, reaffirms the traditional symbolic power of the stupa, but reconsiders its form as both solid and illusory. Yak Tseten took a very different medium—beer bottles—to fashion a large stupa in Tibetan grasslands and then reassembled it at an exhibition space in Beijing several months later.

Tibetan artists have also employed Buddhist texts , important objects of Tibetan Buddhist culture. Tenzing Rigdol’s radical engagement with Tibetan Buddhist texts in his 2009 performance work Scripture Noodles is documented in a video. He sliced up pages of Tibetan Buddhist texts as noodles, stir-fried them with vegetables, and consumed this dish, disposing of the leftovers in a trash bin. The video caused a considerable backlash from some Tibetans, who felt the artist disrespected Tibetan culture and Buddhist teachings, which the pages literally represent.

Contemporary artists often intentionally combine religious forms with the profane or mundane. Kesang Lamdark, based in Switzerland, uses found ordinary objects in -like installations and tantric montages, and includes depictions of sex in his light boxes, needle-pierced metallic surfaces, and mirrors. An apparent freedom in modifying the sacred images often raises fiercely protective and angry feelings in some viewers. This sort of religious “censorship” may be expected and extends to the works that use images considered sacred in mundane contexts, as traditionally these were separate areas of human experience. For Tibetan artists, no matter where they practice, such explorations often relate to the notion of cultural identity.

Like-minded artists working in Lhasa have organized collectives to explore their identity as Tibetan contemporary artists, to share and grow in their individual practices while jointly experimenting with contemporary art forms.

The Sweet Tea House movement grew out of the first exhibition of modern Tibetan painting, presented in a tea house in 1985 (fig. 3). The pioneering work of its organizers—Gonkar Gyatso, Angsang, Angqing, and Aibu—and others, shown in several exhibitions in Lhasa, had a profound impact on the development of contemporary Tibetan art.

Gonkar Gyatso (b. 1961, Lhasa); 对面的山 [Opposing Mountains]; 1986; gouache on canvas; 34¼ × 45¼ in. (87 × 115 cm); photograph courtesy Gonkar Gyatso

Another group of artists established the Gedun Choephel Artists’ Guild in response to formulaic state-sponsored exhibitions in Lhasa in the late twentieth century and to mark the one-hundredth birth anniversary of the renowned Tibetan intellectual and self-taught painter Gendun Chopel (1903–1951) in 2003 (fig. 4). It became a platform for free creative expression and artistic dialogue. In their statement, the artists declare their respect for traditional Tibetan art and culture and a desire to express themselves in whatever medium they choose as contemporary artists in a changing modern world. Gade’s Ice Buddha is one manifestation of such work.

Jiang Hailong (b. 1974, China); Group Portrait of Gedun Choephel Artists’ Guild; 2017; from left: Tenchoe, Weidong (Yak Tseten), Tse Kal, Tsewang Tashi, Angsang, Lu Zungde, Gade, Tserang Dhandrup, Nortse, Tsering Nyandak, Somani, Jhamsang, Huang Zhaji (Huang Yaohong), Huang Jialin, Penpa, Anu Shelkawa (not all Guild members are featured); photograph courtesy Jiang Hailong

Navigating complexities of contemporary life, responding to cultural changes while communicating the sense of being through their art—these are constants among many artists who create in Tibetan areas and around the world. A momentous event in 2006—the arrival of Beijing-Lhasa railway service—has altered the city of Lhasa, bringing more visitors from mainland China and foreign tourists. In this changed reality, in 2007 a few artists established the Melong (Mirror) group. In 2009 another eight Tibetan painters founded Botson (Tibetan paint); they hold annual exhibitions in Lhasa and participate in shows elsewhere in China and abroad.

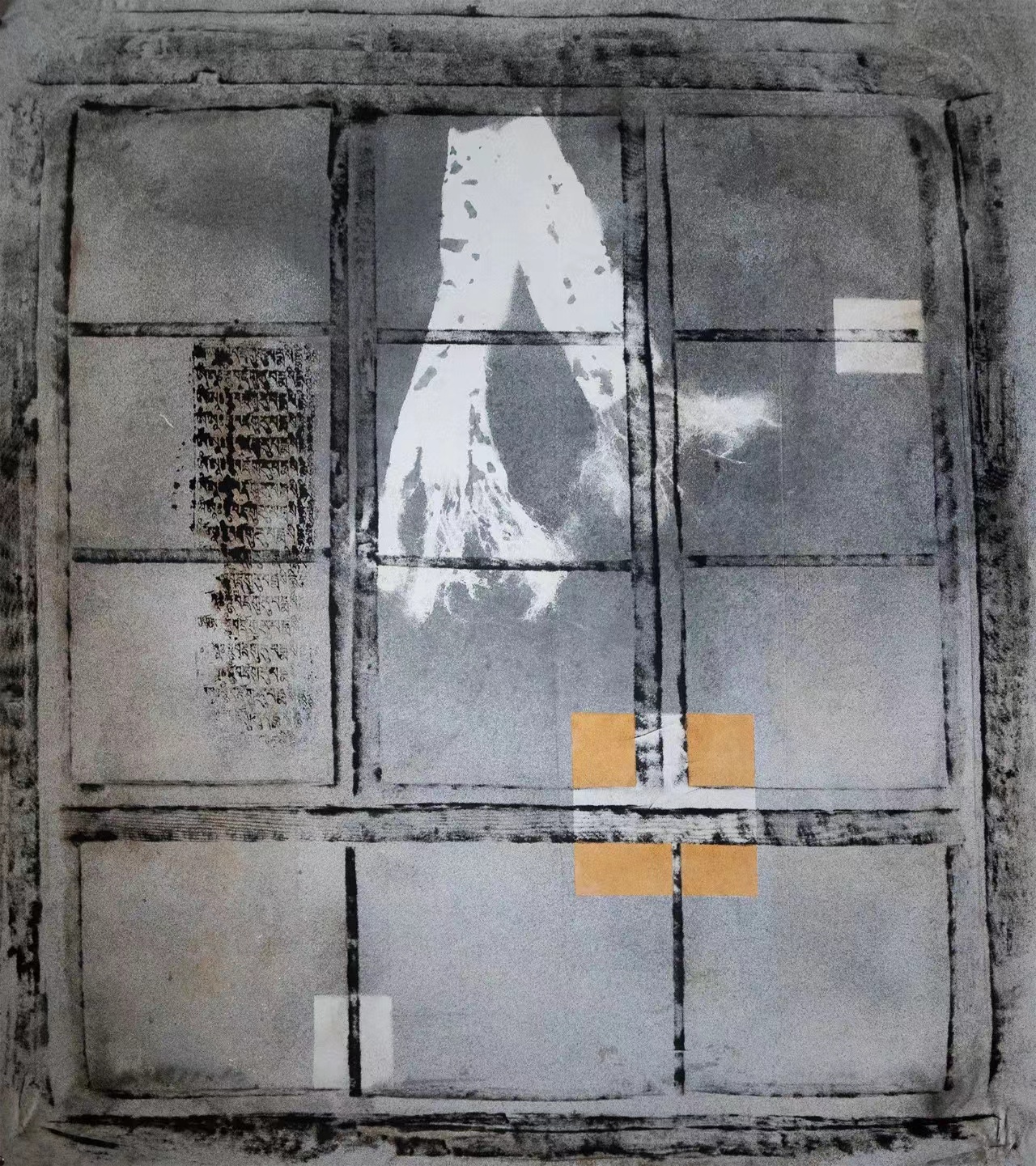

Many address in their art the importance of Tibetan language and cultural history. Sodhon’s use of Tibetan letters as major elements in his painting and Nortse’s installation 30 Letters of the Tibetan alphabet made out of rusting iron comment on the fragility and erosion of their native language. Some artists explore the art of calligraphy, using flowing lines of to deliver meaning or form abstract images. In recent work, the artist Penpa created rubbings of windows from demolished traditional buildings in Lhasa’s Tolung neighborhood as tactile memories of the lives lived in those buildings (fig. 5).

Penpa (b. 1974, Lhasa); Window No. 1; Tolung, Lhasa; 2020; mixed media; 45-5/8 × 29½ in. (116 × 75 cm); photograph courtesy Penpa

Scorching Sun of Tibet, a 2010 exhibition at the Songzhuang Art Museum in Beijing, displayed a broad range of artistic sensibilities in diverse forms and mediums (fig.6). Cocurated by Gade and Li Xianting, a well-known art critic, with attention to the works’ contemporary significance, it is the most comprehensive, self-reflexive exhibition of contemporary Tibetan art to date. In 2016 Gade and Nortse opened the Scorching Sun Art Lab in Lhasa to provide a platform for local groups and young artists to show their work (fig. 7). The Lab cooperated with galleries in mainland China running an artist-in-residence exchange program until its closure in 2019.

Installation view of the exhibition Scorching Sun of Tibet, Beijing, 2010; photograph courtesy Gade

Installation view of the exhibition Tibet Contemporary, curated by Nortse, Scorching Sun Art Lab, Lhasa, May 2017; photograph courtesy Nortse

Many exhibitions organized in the West and India, in commercial galleries and public spaces, continue to be curated with formulaic notions of Tibetan contemporary art as juxtaposed with traditional art and as seen through the lens of Tibetan identity.

Tibetan artists who are internationally active are aware of and critically responsive to external expectations of spirituality and “Tibetan-ness” in their art. Their work often focuses on the complexity and realness of their experiences. Tenzing Rigdol, based in the United States and India, in his Our Land, Our People (2011), experimented with a site-specific installation. Soil from Tibet was secretly brought to India for Tibetans living in exile to stand on, symbolically and physically connecting them with their land. Rigdol’s communal and interactive project is a social commentary that also reflects the artist’s own examination of identity. Gonkar Gyatso’s Family Album (2016) shows the multiple identities of his family members, who include a member of the Communist Party, a Buddhist nun, an artist, and others. He questions the monolithic view of Tibetan-ness in the multilayered and complex contemporary Tibetan world. Photographs by Nyema Droma (Nyedron) of young international Tibetans at the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford in 2019, created in response to the early twentieth-century photographs of Tibet and Tibetans by the British, showed very different but “just as cool” Tibetans.

In 2003 Lhasa witnessed the first exhibition dedicated to paintings and ideas of six women artists, Dedron, Chime Dolkar, Tsering Lhamo, Tsering Dolma, Zhang Linhong, and Zhang Ping. In 2017 Gade curated the exhibition Her in Lhasa, intended as the first in a series of shows to highlight women in different creative fields—visual art, literature, music, film, dance, and fashion. It included photographs by Nyema Droma and paintings of Dedron, Tsering Lhamo, Tsering Dolma, and Dangsel Dawa (fig. 8). In 2020 the first solo exhibition in Lhasa of a Tibetan woman painter, Tsering Dolma’s Dance! Dance! Dance!, traced her creative journey from the 1980s to the present and introduced younger viewers to contemporary work by women artists in Tibet.

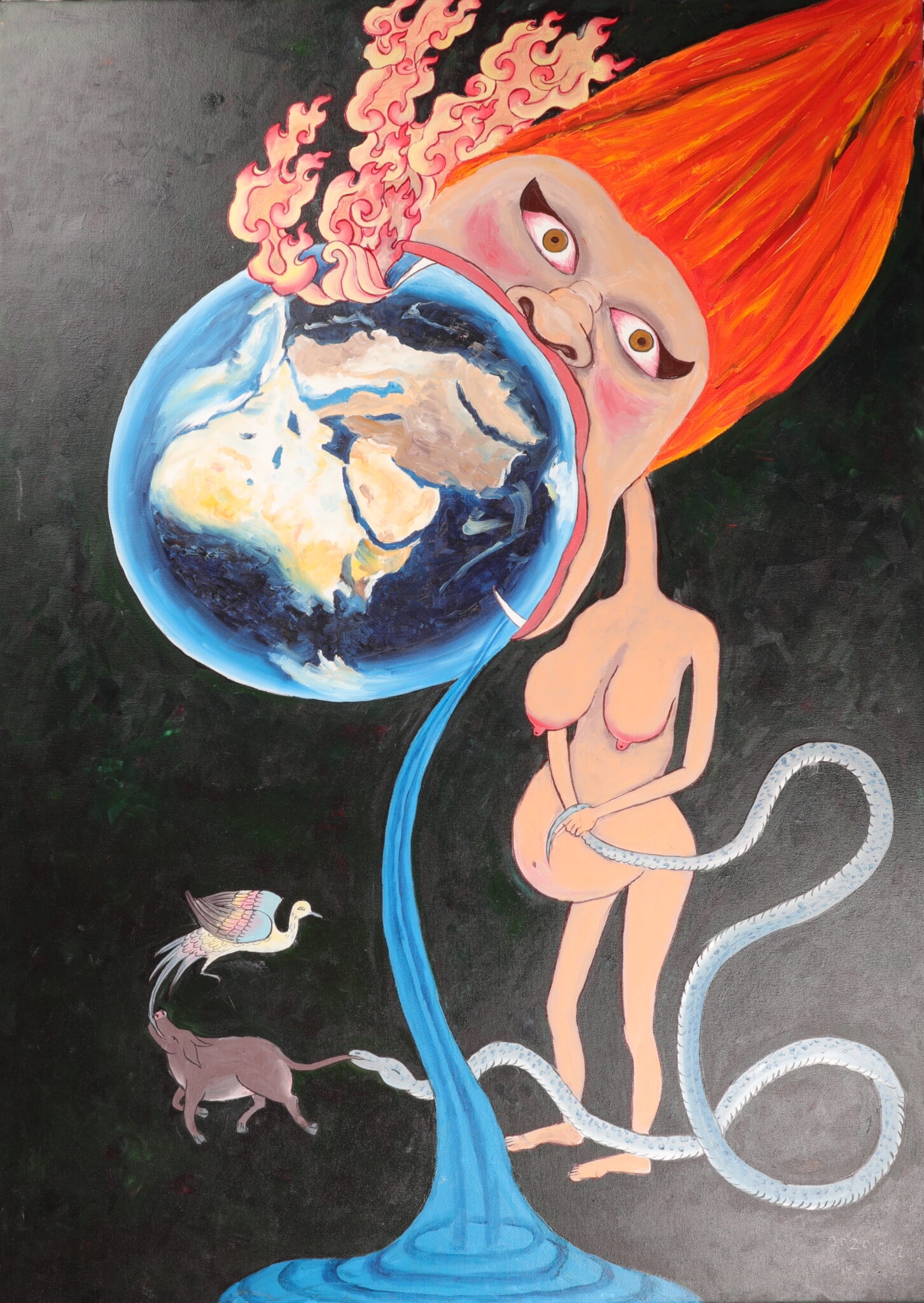

Tsering Dolma (b. 1966, Lhasa); Desire; Lhasa; 2020; oil on canvas; 55 1/8 × 39 3/8 in (140 × 100 cm); photograph courtesy Tsering Dolma

Identity has never been the only framework for Tibetan artists; they have assembled for other reasons and causes, such as the collaborative ecological project Keepers of the Water organized by Betsy Damon in Chengdu (1995) and Lhasa (1996). A series of art events revealing the interconnectedness of humans and environment, the Lhasa presentation of Keepers of the Water took place along the Kyichu River in August–September 1996. Artists from Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Xi’an, Tibet, Switzerland, and the United States came together to raise awareness about water protection through installation and performance art. The Lhasa-based artists engaged the local community to make art as an embodied practice of awareness about ecology (fig. 9). Much of their work was inspired by Tibetan culture, land, and environment.

Gade (b. 1971, Lhasa); installation work in the exhibition Keepers of the Water; Lhasa, 1996; photographer unknown, image courtesy Tsering Nyandak

Tibetan artists around the world continue exploring these notions. Sonam Dolma Brauen, unlike most Tibetan artists, does not generally employ traditional Tibetan cultural markers in her work. She uses the language of modern art to address themes that are informed by her worldview. Her installation works, such as My Father’s Death (2010), Boomerang (2010), and DNA (2013), are deeply personal and universal in their themes. Marie-Dolma Chophel’s paintings map and relate micro- and macrocosmic terrains, from a single atom to distant galaxies—atmospheric depictions of landscape and the cosmos, or a flux of the concrete and the abstract, natural and artificial, real and virtual, personal and shared. Palden Weinreb’s works—in delicate pencil drawing or large, glowing sculptures—embrace and mine diverse cultural and collective ideas and forms. Tsherin Sherpa’s Wish-Fulfilling Tree (2016), is a response to the devastating 2015 earthquake in Nepal, but also a communal acknowledgement of universal human suffering caused by a natural disaster. Nortse’s work, 2020, created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, is an overwhelming, looming sphere that seems to represent the globe and the virus; it conveys the sense of tangled lives, broken structures, and emergency (fig. 10).

Nortse (b. 1963, Lhasa); 2020; Lhasa; 2020; mixed media; 94½ × 94½ in. (240 × 240 cm); photograph courtesy Nortse

Although commercial galleries no longer play a dominant role in commissioning Tibetan artists, less representation does not affect the younger generation of artists and curators engaging with global trends in the digital age. Lhasa remains a cultural center for contemporary artists of different generations from within and without the Tibet Autonomous Region. An alternative art space founded in 2021, Lhasa Art Box (LAB), is a platform for diverse local artists to present their work and communicate with the outside world. In October 2021 LAB organized the citywide Sweet Tea House Art Festival, focused on the works of young artists and creatives.

All generations of Tibetan artists actively respond to the realities in which they live with distinct creative expressions, experimenting in new media and formats, and seek to engage in global discourse. Artists in Bhutan, Nepal, and Mongolia create in their own artistic spheres and in recent years have expanded into the global art scene.

The Kyichu is a tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, which becomes the Brahmaputra upon reaching India.

The use of ephemeral mediums in Tibetan Buddhist culture directly relates to Buddhist notions of impermanence and performative aspects of offerings, such as torma offerings.

We perceive objects, forms, sensations, and thoughts as real in a relative sense, but ultimately everything is nondual and empty of unchanging, independent existence. See Donald S. Lopez Jr, The Story of Buddhism: A Concise Guide to Its History and Teachings (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 2002), 27–30, 37–129.

See Leigh Miller, “A Buddhist Mickey Mouse,” in Figures of Buddhist Modernity in Asia, ed. Jeffrey Samuels, Justin McDaniel, and Mark Rowe (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2016), 163–64.

Clare Harris, “In and Out of Place: Tibetan Artists’ Travels in the Contemporary Art World,” Visual Anthropology Review 28, no. 2 (2012): 54–58.

For more examples of the buddha’s form in contemporary Tibetan art, see H.G. Masters and Elaine W. Ng, eds., Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art, Exhibition catalog (Hong Kong: ArtsAsiaPacific, 2013), 45, 59, 91, 104, 124, 144–45; Trace Foundation, Transcending Tibet: 30 Contemporary Artists Explore What It Means to Be Tibetan Today, Exhibition catalog (New York: Trace Foundation, 2015), 120–21, 164; Martin Brauen, “The Buddha in a Shopping Bag,” in Transcending Tibet: 30 Contemporary Artists Explore What It Means to Be Tibetan Today, Exhibition catalog (New York: Trace Foundation, 2015), 66–77.

For still photographs, see David Elliott, “What Is . . . ? Pitfalls of Identity in a Slippery Age,” in Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art, ed. H.G. Masters and Elaine W. Ng, Exhibition catalog (Hong Kong: ArtsAsiaPacific, 2013), 19–30, 30; H.G. Masters and Elaine W. Ng, eds., Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art, Exhibition catalog (Hong Kong: ArtsAsiaPacific, 2013), 160–61.

For more on his diverse work, see Kesang Lamdark, Kesang Landark (Milan: Skira, 2021).

Conversation with Gade, October 1, 2019.

Beginning with state-sponsored exhibitions in the 1970s, Tibet and Tibetans have been frequent subjects of realist oil paintings by Chinese artists who explored regions new to them for artistic inspiration; some Tibetan artists were also trained in this mode of painting and have followed similar formulas for depicting Tibet, resulting in stereotypical representations of Tibet in visual art. On Gendun Chopel and his role in Tibetan modern art, see Donald S. Lopez Jr, Gendun Chopel: Tibet’s First Modern Artist (New York: Trace Foundation’s Latse Library, 2013).

See Filippo Salviati, “Tibetan Art between Past and Present: Dialogue with the Past; An Overview of Contemporary Tibetan Artists,” in Tibetan Art between Past and Present: Studies Dedicated to Luciano Petech, Proceedings of the Conference Held in Rome on the 3rd of November 2010, ed. Elena De Rossi Filibeck (Pisa: Fabrizio Serra Editore, 2012), 159; Gade, “Quoted in “Gedun Choephel Artists’ Guild,” Asianart.com, 2003, https://www.asianart.com/gendun/about.html.

In addition to the artists’ self-organizing movements and their exhibitions, commercial galleries, such as Rossi and Rossi in the United Kingdom and Peaceful Wind in the United States, have represented Tibetan artists since the early years of the twenty-first century.

Lhasa Train exhibition at the Peaceful Wind Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico (September–October 2006), marked this occasion. The paintings commissioned in advance from the artists of the Gendun Choephel Artists’ Guild demonstrated the anticipation, hopes, and imaginings of how this new reality would change Lhasa.

See also Clare Harris, “In and Out of Place: Tibetan Artists’ Travels in the Contemporary Art World,” Visual Anthropology Review 28, no. 2 (2012): 160–61.

In addition, the early 2010 exhibition Tradition Transformed: Tibetan Artists Respond, hosted at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art in New York, attempted to gather works by Tibetan artists active in the West, a few Tibetan artists from Lhasa, and Nepal.

Li Xianting, Lie Ri Xi Zang—Xi Zang Dang Dai Yi Shu Zhan 烈日西藏─西藏當代藝術展 [Scorching Sun of Tibet: Contemporary Art Show], Exhibition catalog (Beijing: Songzhuang yishu guan, 2010).

For instance, Tibetan Encounters: Contemporary Meets Tradition (London, UK, 2007), Beyond the Mandala: Contemporary Art from Tibet (Mumbai, 2011), Tradition Transformed: Tibetan Artists Respond (New York, 2010); and Boundless: Contemporary Tibetan Artists at Home and Abroad (San Francisco, 2018). Identity-focused exhibitions include Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art (New Paltz, NY, 2013) and Transcending Tibet: 30 Contemporary Artists Explore What It Means to Be Tibetan Today (New York, 2015). See H.G. Masters and Elaine W. Ng, eds., Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art, Exhibition catalog (Hong Kong: ArtsAsiaPacific, 2013); Trace Foundation, Transcending Tibet: 30 Contemporary Artists Explore What It Means to Be Tibetan Today, Exhibition catalog (New York: Trace Foundation, 2015).

For more on complex preconceptions about Tibetan culture, see Martin Brauen, Dreamworld Tibet: Western Illusions, trans. Martin Willson (Boston: Weatherhill, 2004).

A film made in 2013 about this project, Bringing Tibet Home, is available on streaming platforms. Rigdol has also established an artist residency program in Dharamsala, India.

Nyedron in conversation, May 24, 2019.

For instance, Tsewang Tashi’s Liberation, saving fish by releasing them into the river, was based in Buddhist practice, as was Water Burial by Tsering Lhamo.

See Regina Höfer, “Sichtbarmachung der Leerheit: Sonam Dolma und die zeitgenössische tibetische Abstraktion (Making emptiness visible: Sonam Dolma and contemporary Tibetan abstraction),” Masala Newsletter: Virtuelle Fachbibliotek Südasien 6, no. 2 (2011): 9–16.

Brauen, Martin. 2015. “The Buddha in a Shopping Bag.” In Trace Foundation, Transcending Tibet: 30 Contemporary Artists Explore What It Means to Be Tibetan Today, 66–79. Exhibition catalog. New York: Trace Foundation.

Kesang Lamdark with contributions by David Elliott, Regina Höfer, Andy Cohen, and A. C. Kupper. 2021. Kesang Lamdark. Milan: Skira.

Gade. 2016. “A Broken Flower Blossoming in the Cracks: Tibetan Artist Gade Talks about Contemporary Tibetan Art.” Interview by Tsesung Lhamo, translated by High Peaks Pure Earth. High Peaks Pure Earth website. https://highpeakspureearth.com/a-broken-flower-blossoming-in-the-cracks-tibetan-artist-gade-talks-about-contemporary-tibetan-art/.

Yangla Gesang, Yuyuan (Victoria) Liu, Elena Pakhoutova, “Ice Buddha: Tibetan Artists’ Contemporary Practices,” Project Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, 2023, http://www.rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/ice-buddha.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Cum nihil placeat pariatur deserunt eius ullam incidunt maxime sunt ipsam. Ipsa, provident, laudantium, rem assumenda laboriosam veniam autem voluptas sint officia distinctio enim aut explicabo fuga animi voluptatum earum recusandae excepturi atque dignissimos iste? Exercitationem, praesentium eum. Harum ut maiores expedita exercitationem perspiciatis soluta aperiam dolores natus unde, sequi vitae debitis ex aliquam quas eum reprehenderit esse. Cumque amet et earum necessitatibus, repellendus ullam ducimus corporis architecto culpa placeat eum odit cum iure illo vitae rerum! Ullam et suscipit culpa? Eos voluptatum laudantium iste vero impedit adipisci maxime magni natus voluptatibus.

Get the latest news and stories from the Rubin, plus occasional information on how to support our work.